maps

maps

04/23/02

maps

maps

| Wildflowers of the Westborough Reservoir |

|

04/23/02 |

|

Between 1969 and 1971, the town acquired 144 additional acres of conservation land to protect the Reservoir's watershed after the construction of the Mass Pike in the late 1950s. The area along Bowman Street was replanted with over 1,000 pines, and nature trails were established to create a conservation area, which town residents still enjoy today. The Bowman Street Conservation Area is accessible from a parking lot on Bowman Street and from Minuteman Park, established along Upton Road in 1975.

The Westborough Reservoir and Bowman Street Conservation areas are laced with trails through varied

terrain, which provides a range of growing environments for wildflowers. The plants range from

commonplace to rare and protected. The 80 or so wildflowers shown here are presented roughly in the

order in which they bloom, month by month, from March through October. Similarly, a separate article

presents other local wildflowers found in and around

Westborough.

|

|

|

Pussy Willow, Salicaceae family (Salicaceae)

Pussy willow (Salix discolor) is a clumped, shrubby plant that heralds the coming of spring with small, furry, gray catkins. It often starts to bloom in early March at the Reservoir, marking the beginning of wildflower season. The catkins are actually dense clusters of very simple flowers that lack petals.

Pussy willow bears male and female flowers on separate plants. After the furry catkins have been out for a while, male or female flower parts emerge from them. Insects carry the sticky yellow pollen from male flower to female flower as they forage.

Historically, the bark of most willows was used to relieve pain and lower fevers. Willow bark contains a substance that is chemically related to aspirin, which has since replaced it in modern medicine. Both the bark and the catkins of pussy willow were collected in the spring for use in medicines.

Skunk Cabbage, Arum family (Araceae), Native

|

Foul-smelling when stepped on or broken, skunk cabbage is pollinated by early bees and by

flies. Recent research shows that parts of the plant generate heat as they come up, perhaps

helping the plant to grow through snow or to attract its pollinators. A few weeks after the

blossoms appear, the familiar green

leaves unfurl and grow large.

Marsh Marigold, Buttercup family (Ranunculaceae), Native

|

The flowers of marsh marigold look yellow to human eyes, but bees see them differently. They see ultraviolet

(UV) wavelengths that we do not perceive. To bees, the marsh marigold flowers have a dark center, like a

bull's-eye, that helps to guide them to nectar. The flowers absorb UV light especially strongly toward the

center, so they look darker there to the bees.

Common Dandelion, Composite or Daisy family (Compositae), Alien

|

| |

Although a variety of insects visit the yellow flowers, looking for nectar early in the season, dandelion flowers produce seeds without being pollinated. These seeds are genetically the same as the parent plant. They appear in the familiar fuzzy ball-shaped head and blow away on the wind.

People have long used dandelions for food and medicine. The deep taproot, which helps the plant

survive nature's droughts and homeowners' digging, has been an ingredient in medicines and salads.

Young dandelion leaves have also gone into salads and been boiled as greens. The flowers and flower

buds have been fried in batter. The flowers are also reputed to make a sweet wine.

Northern Downy Violet, Violet family (Violaceae), Native

Windflower or Wood Anemone, Buttercup family (Ranunculaceae), Native

Common Blue Violet, Violet family (Violaceae), Native

|

|

Violets have historically been regarded as symbols of innocence and modesty. Greeks, Romans, and medieval Christians all had legends involving violets. Violets have also had numerous medicinal uses, going back hundreds of years. The flowers contain sugar and pectin and have been used in candy and gelatins and as a food dye. The leaves have been used in salads. Research shows that leaves of the common blue violet are sources of both vitamin C and vitamin A.

Common blue violets are among the kinds of violet that have a mutually beneficial relationship with ants. These violets produce seeds with nutritious, pale-colored attachments on them, and ants are so attracted to these special food packets that they carry the seeds back to their underground nests. There the ants eat the food packets and discard the seeds in unused tunnels, effectively planting them in a protected, rich environment. The ants get food, and the next generation of violets gets a head start in life.

Besides certain violets, many other spring-blooming forest plants have their seeds dispersed by ants. They include bloodroot ( Sanguinaria canadensis), wild ginger (Asarum canadensis), sharp-leaved hepatica ( Hepatica acutiloba), wood anemone (Anemone quinquefolia), Dutchman's-breeches (Dicentra cucullaria), trout lily (Erythronium americanum), celandine (Chelidonium majus), and large-flowered trillium (Trillium grandiflorum). By some estimates, more than half of the spring wildflowers in certain environments are distributed by ants in this way.

Common blue violets look quite similar to marsh blue violets

(Viola cucullata), except that marsh blue violet blossoms are usually darker at the center. Another

notable difference is the height of the flower stems. The flowers of common blue violet have shorter stems

and tend to be found among the leaves. Marsh blue violet has longer stems, so the blossoms stand well above

the heart-shaped leaves.

Common Winter Cress, Mustard family (Cruciferae), Alien

|

Some of the earliest yellow of spring comes from common winter cress (Barbarea vulgaris). Usually regarded as a weed, it blooms along the edges of roads, open fields, and parking lots, where its yellow spikes make a welcome sight. The lowest flowers on the spikes open first and then form seed pods as new flowers bloom further up.

Like other members of the mustard family, common winter cress has served as a source of greens.

Its young leaves appear in late winter or early spring, before much else is available, but they

become bitter by the time the plant flowers. Native Americans used tea from the leaves as a

cough medicine.

Celandine, Poppy family, Poppy Subfamily (Papaveroideae), Alien

|

The stems and leaves are notable for their acrid yellow sap, which can stain and irritate the skin. In earlier days, people applied the sap to warts to remove them. This practice earned celandine the tongue-twisting name "wartwort," meaning "wart plant" (since "wort" is an Old English word for plant.) The sap also had numerous other medicinal uses, many involving the skin or eyes.

Celandine came to the east coast of this continent from Europe and east Asia and has been migrating westward

across the country. In Chinese and Russian folk medicine, it was reputed to work against cancer. More

recently, it has been found to contain at least four chemicals with anti-tumor activity.

Gay Wings or Fringed Polygala, Milkwort family (Polygalaceae), Native

| Small spots of pinkish purple among the dead leaves on the ground in mid-May turn out to be gay wings (Polygala paucifolia), also called fringed polygala. These small evergreen plants, about four inches high, may have roots more than a foot long. The inch-long flowers have a delicate bushy fringe and two purple wings. |

|

Starflower, Primrose family (Primulaceae), Native

| In mid-May, the starflowers (Trientalis borealis) open. These plants dot the ground in wooded sections of the Reservoir. A pair of delicate, star-like flowers opens above a whorl of green leaves on each plant. If the weather does not get too warm, starflowers can remain in bloom for a couple of weeks. |

Wild Lily-of-the-Valley, Lily family (Liliaceae), Native

|

By mid- to late May, wild lily-of-the-valley (Maianthemum canadense) carpets woodsy sections of the

Reservoir. Also called Canada mayflower, these small plants often spread by underground runners and grow

in dense beds in the woods. They have small clusters of tiny creamy white flowers. Later they produce

berries that turn from white to pale red.

Native Americans used tea made from the plant for headaches and as a soothing gargle for sore throats.

The root served as a charm to win games.

|

Bluet, Bedstraw family (Rubiaceae), Native

|

These small flowers come in two forms. A patch usually contains flowers of one form or the other. Each flower has both male and female parts, but in one form, the pollen-bearing male parts are tall while the pollen-receiving female parts are short. In the other form, the situation is reversed, with short pollen-bearing male parts and tall pollen-receiving female parts.

When pollinating insects rummage around in the flowers, pollen sticks to them in different patterns,

depending on the height of the flowers' male parts. As the pollinators move to another patch of flowers,

this patterning makes pollen from tall pollen-bearing parts available to flowers with tall pollen-receiving

parts, and pollen from short pollen-bearing parts available to flowers with short pollen-receiving parts.

This arrangement promotes cross-pollination and hinders self-pollination, leading to a healthier new

generation of plants.

Northern White Violet, Violet family (Violaceae), Native

| In May, when violets show up in lawns and gardens, northern white violets (Viola Pallens) nestle among grasses and dead leaves at the Reservoir. The five petals of this small, easily recognized flower are arranged conveniently for insect pollinators. The two upper petals and two side petals act as flags to attract insects, and the bottom petal gives them a place to land. The colored veins in the bottom petal lead insects toward the nectar that can be found in a spur at the back of the bottom petal. |

|

Eastern Wild Columbine, Buttercup family (Ranunculaceae), Native At times, eastern wild columbine (Aquilegia canadensis) has appeared in the woods at the Reservoir, although it favors rocky cliffs and outcroppings. Its intricate, red-and-yellow blossom resembles a lantern and has long tube-like spurs that contain nectar. It is pollinated by bumblebees and hummingbirds, which can suck the nectar from the spurs. Other bees and wasps sometimes chew holes in the ends of the spurs to get at the nectar. This is the only wild columbine of the eastern United States, although about twenty other species--often with blue, white, or yellow flowers--grow in the west, especially in the Rocky Mountains. Most cultivated garden varieties of columbine are derived from a European species.

|

|

Pink Lady's Slipper or Moccasin Flower, Orchid family (Orchideaceae), Native

|

|

|

Like many other orchids, pink lady's slipper needs its growing conditions to be just right. It is very

difficult to grow from seed or to transplant. The soil must be quite acidic, and it must contain

a particular type of fungus (Rhizoctonia) which helps the seeds germinate and grow. In turn, the

seedlings supply the fungus with food from photosynthesis. This complex symbiotic relationship

helps to make the plant uncommon. Lady's slipper plants can take years to mature, and their

average life span is about 20 years.

Wild Geranium, Geranium family (Geraniaceae), Native

In moist, partly shaded, wooded areas, wild geranium (Geranium maculatum) plants produce their light purple flowers in late May and early June. The one-inch blossoms are relatively large for a woodland wildflower, and the plant has large, deeply cut, five-part leaves. Its pollen is an unusual bright blue, rather than yellow or orange as in most plants. Another common name for the plant is cranesbill, which refers to the graceful shape of its long, slender, curved seedpods. The pods develop as the flower petals wilt and drop off, as the photo shows. When the seeds are ripe, the pods pop open and send the seeds flying into the surroundings. Once on the ground, a seed can push itself along as its "tail" alternately dries out and curls and then absorbs moisture and straightens out. Wild geranium has a long history of medicinal use, going back to early Native Americans. The tannin in its leaves made it useful as an astringent and styptic. It was also used in mouthwashes and gargles. This wild geranium is a native of North America, although some similar species are not. It is not related to to the familiar "geraniums" that are so popular in hanging pots and flower boxes. These plants are pelargoniums, originally imported for gardens from South Africa. |

Lance-leaved Violet, Violet family (Violaceae), Native

|

Lance-leaved violet (Viola lanceolata) is a white violet with long, narrow leaves, as the name

suggests. It usually grows in swamps or wet places.

Besides reproducing by seed, lance-leaved violets can spread by sending out above-ground runners from which

new plants grow. All the plants in a patch of these violets may in fact be one individual. This type of

reproduction gives this violet a way of spreading quickly in a favorable location.

Bristly Locust or Rose-acacia

|

|

|

Indian cucumber-root (Medeola virginiana) blooms discretely in wooded areas in early June. The small spiderly flowers dangle from the plant's upper whorl of leaves. The plant is a member of the lily family.

The name refers to the Native American practice of digging the roots for food. The root is crisp and tastes and smells like cucumber. Native Americans also used to spit chewed root on their hooks to get fish to bite.

Birds like the berries, which turn bluish when they ripen in late summer. At that time, the base of

the leaves loses color or turns red, signaling the presence of berries.

False Hellebore or Indian Poke, Lily family (Liliaceae), Native

|

In late spring, the cornstalk-like plants of false hellebore (Vertrum viride) quickly grow tall in swampy areas. Their large pleated leaves are distinctive with several parallel ribs. The plants produce numerous greenish flowers crowded on graceful branches and then die back after flowering. Indian poke is another common name for this member of the lily family.

False hellebore is toxic to grazing animals and has been shown to produce birth defects in sheep.

Greenish-flowered Pyrola, Wintergreen or Pyrola family (Pyrolaceae), Native

|

|

|

|

Blue Flag Iris, Iris family (Iridaceae), Native

|

|

|

In early June, when cultivated irises begin to bloom in Westborough's gardens, the blue flag iris (Iris versicolor) appears at the water's edge at the Reservoir. The showy flowers are called flags because European rulers often decorated their banners, flags, and crowns with with designs based on the shape of the iris flower. In fact, the fleur-de-lis motif was derived from a kind of white iris.

The nectar in wild irises attracts a variety of insects,

but bumblebees are typically the ones that successfully transfer pollen from one flower to

another as they push inside.

Blue-Eyed Grass, Iris family (Iridaceae), Native

|

|

|

In early June, woodland jack-in-the-pulpit (Arisaema atrorubens) appears in damp areas near streams and swamps, often in places where its relative, skunk cabbage, also grows. It is named for its resemblance to an old-fashioned pulpit with a "preacher" inside. The plant has also been called Indian turnip because Native Americans processed the bitter, sometimes caustic root in various ways so they could use it for medicine and food. Jack-in-the-pulpit plants live for several years, and the reproductive role of a plant changes with its age. Early in the life of a plant, most of its tiny flowers--clustered on the club-like "preacher"--are pollen-producing male flowers. A few years later, when the plant is larger and stronger, with more resources for seed-bearing, it produces mostly female flowers. In its later years, the plant may switch back to producing mostly male flowers. Some jack-in-the-pulpits at the Reservoir are all green, instead of striped and brownish as shown here. The plants' clusters of bright red berries are notable in late August or early September, before the autumn leaves turn. |

Sheep Laurel, Heath family (Ericaceae), Native

|

The dark pink, cup-like flowers appear in clusters. As the photo shows, each flower has ten stamens

tipped with pollen-bearing anthers that are tucked into pockets in the flower petals. When an insect

pokes at the center of a flower, the stamens spring out of the pockets, sprinkling pollen on the

insect.

Nodding Trillium, Lily family (Liliaceae), Native

| Nodding trillium (Trillium cernuum) blooms in some damp areas at the Reservoir in June. The white, three-petaled flowers face downward, hidden as they dangle beneath the trillium's characteristic three leaves. Like most trilliums, this one has a mildly unpleasant odor that attracts flies as pollinators. |

Pasture or Carolina Rose, Rose Family (Rosaceae), Native

|

Just as mid-June is the time for roses in Westborough's gardens, so it is at the Reservoir. In wooded areas near the water, especially on peninsulas, wild pink roses such as pasture rose (Rosa carolina) bloom and perfume the warm air with their delicate fragrance. The petals are fragrant even after they have fallen from the blossoms.

The fruits, or rose hips, develop through the summer and turn reddish in the fall, lasting on the bushes

into the winter. Roses have long provided food, going back to the Native Americans. Rose hips are

rich in vitamin C. They have been made into jam, tea, and candy.

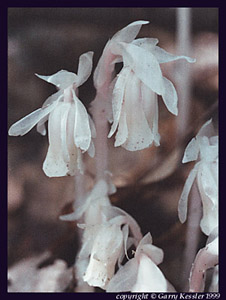

Indian-pipe, Wintergreen or Pyrola family (Pyrolaceae), Native

|

Indian pipes are saprophytic plants, living off dead plant matter, especially decaying tree roots.

They get their nutrients with the help of various soil fungi but are not a fungus themselves.

They are flowering plants that have lost their leaves and their green chlorophyll in the course of

evolution. Indian pipes are native to North America and can be found across the continent.

Birdfoot Trefoil, Pea family (Leguminosae), Alien

|

A small, showy member of the pea family, birdfoot trefoil (Lotus corniculatus) has clusters of bright

yellow flowers. The name comes from the arrangement of the seed pods, which suggest a bird's foot. Like

other legumes, this plant has a symbiotic relationship with certain soil bacteria that adds nitrogen to the

soil in a form that plants can use as a nutrient.

Birdfoot trefoil also prospers in the lawn-like areas around shopping center parking lots in Westborough.

It first blooms in June but continues throughout the summer if there is enough rain.

Yellow Goat's-beard, Composite or Daisy family (Compositae), Alien

|

Like its relative, the dandelion, yellow goat's-beard flowers transform themselves into round, feathery seedheads. These sizable blowballs are much larger and more striking than those of the dandelion.

In the past, yellow goat's-beard had various medicinal uses. It also had value as a food. Its roots were

eaten like parsnips, and its stalks were eaten like asparagus.

Bittersweet Nightshade, Nightshade or Potato family (Solanaceae), Alien

|

In spite of the nightshade name, the nightshades at the Reservoir are not the true "deadly nightshade"--or belladonna (Atropa belladonna)--of literature and lore. Belladonna grows in central and southern Europe and is rarely found in North America. It contains a poisonous chemical, atropine, and all parts of it are poisonous. In contrast, the nightshades at the Reservoir have histories of medicinal use, although their berries or other parts may cause a stomachache. To be on the safe side, children should not put the berries in their mouths.

Bittersweet nightshade may get its name from the taste--first bitter, then sweet--that comes from chewing the leaves. A substance called dulcamarine is responsible for this experience. The plant also contains small quantities of another chemical, solanine, which contributes to various effects that have been considered both medicinal and poisonous.

The small flowers of bittersweet nightshade have a distinctive look, with turned-back petals and a cone-shaped beak. Gardeners may notice that they are similar to flowers of the tomato plant (Lycopersicum esculentum), which is in the same family, the nightshade or potato family (Solanaceae). (Tomatoes were once believed to be poisonous.) Other plants in this family include the potato (Solanum tuberosum), the eggplant (Solanum melongena), and tobacco (genus Nicotiana).

Nightshade flowers do not produce nectar. Insects feed on the pollen instead. The flowers often point

downward, and bees hang upside-down on the flowers and vibrate their wing muscles to shake pollen out

of the beak.

Daisy Fleabane, Composite or Daisy family (Compositae), Native

|

In spite of its name, daisy fleabane is not useful for killing or chasing away fleas. Its name may be due to its similarity to a European plant, true common fleabane (Inula dysenterica). People used to burn this plant so the smoke would drive away fleas and other insects.

Like most plants in the composite or daisy family, the flowerheads of daisy fleabane are dense clusters

of many small flowers. The 40-70 flat, thin, white "petals" of daisy fleabane are actually separate

flowers of one type. They surround a center consisting of numerous tubular yellow flowers of another

type. Such closely packed flowers are readily pollinated by insects, which may touch hundreds of flowers

as they move across the flowerheads, looking for nectar. The flowerheads typically produce abundant seeds,

which, in the case of daisy fleabane, were once likened to fleas--perhaps another source of the name.

Easy pollination and abundant seeds give composites such as daisy fleabane an advantage in the competitive

world of flowering plants, helping to explain why daisy-like flowers are so common and widespread.

Mortherwort, Mint family, (Labiatae), Alien

|

|

|

Stands of motherwort (Leonurus cardiaca) start to show their clusters of small purple blossoms in late June at the Reservoir and continue to bloom well into July. Motherwort is a tall member of the mint family, growing to five feet or so. Like other mints, it has a square stem, clusters of tiny tubular flowers in the crooks where leaf stalks join the stem, and a pungent aroma.

Originally imported for medicinal uses, motherwort quickly escaped from early colonial gardens and spread

rapidly and widely in North America. It was used to treat heart ailments and was respected as a remedy

for "women's complaints," as its name might suggest. "Wort" is simply an old-fashioned word for

"plant," derived from Old English, and has nothing to do with warts. Motherwort is now often regarded

as a weed, rather than a garden staple.

Common St. Johnswort, St. Johnswort family (Guttiferae), Alien

|

Out west, the plant is known as Klamath weed. It spreads aggressively in some areas, and in places a

moth has been introduced as a biological control to keep it in check.

Common Milkweed, Milkweed family (Asclepiadaceae), Native

Found in open fields at the Reservoir, common milkweed (Asclepias syriaca) produces droopy

clusters of small, unique-looking pinkish flowers. It blooms in the summer, often starting in June.

In the fall, typically in late September or early October, its large, pointed seedpods burst open,

releasing seeds borne on silky, fluffy strands that float on the breezes.

Milkweed is named for its thick white sap. The sticky juice often traps ants and other small crawling insects that climb the stout stems in search of nectar. The sap also contains chemicals known as cardiac glycosides, which make it acrid and unpalatable to grazing animals. The cardiac glycosides can affect animal heart muscle.

|

|

|

|

Milkweed plants typically harbor a diversity of insects. The flowers have a sweet scent, especially at night, and abundant nectar. They attract pollinators such as bumblebees, honey bees, wasps, and butterflies during the day, and moths come at night. Other insects, such as yellow jackets and pale, camouflaged crab spiders, prey upon the pollinators.

At least three insects feed only on milkweed and get a special benefit from doing so. The caterpillar of the monarch butterfly (Danaus plexippus), which is known as a "milkweed butterfly", eats the leaves. The milkweed beetle (Tetraopes tetraophthalmus) feeds on the stems and roots, and the small milkweed bug (Lygaeus kalmii) consumes the seeds. These insects have evolved a tolerance for the milkweed's cardiac glycosides, which in turn make the insects noxious to predators, who quickly learn to avoid toxic meals.

Even after metamorphosis from caterpillar to butterfly, monarchs retain the milkweed's cardiac glycosides in their bodies. They take nectar from other flowers besides milkweed but remain poisonous to birds that would feed upon them. Birds have actually been photographed as they vomit after eating a monarch butterfly.

Milkweed plants typically establish themselves quickly, sinking roots so deeply into the ground that farmers find them hard to get rid of. The original plant spreads slowly by underground runners, forming clumps of plants that are genetically identical. For cross-pollination, milkweed depends on sturdy long-distance travelers, such as bumblebees and butterflies, that can easily fly from one clump to another.

North America has approximately 75 species of milkweed, but most of the 2,000 plants in the milkweed

family are tropical plants.

Spreading Dogbane, Dogbane Family (Apocynaceae), Native

|

In spite of its beauty, the plant is considered poisonous to mammals, including dogs, cows, and humans. Native Americans, however, had numerous medicinal uses for the root. Chemicals that affect the heart have also been extracted from spreading dogbane.

The plant can also be deadly to flies, moths, and other small insects that come for its nectar but are not the right size to pollinate the flowers. These insects can get trapped by their tongues in the flowers and left dangling there.

Spreading dogbane is related to the milkweeds. Like them, it has milky sap and seed pods containing fluffy

fibers with seeds attached. The seed pods form in pairs and open in the fall.

Tall Meadow Rue, Buttercup family (Ranunculaceae), Native

|

Tall meadow rue usually has male and female flowers on separate plants. The flowers lack petals. The

male flowers, for example, are made up of numerous thread-like stamens (male flower parts), which give

the flowers their starry, lacy look.

Swamp Candles or Yellow Loosestrife, Primrose Family (Primulaceae), Native

|

In wet years, patches of swamp candles (Lysimachia terrestris) may appear on wet, sunny shores

at the Reservoir. Their spikes of star-shaped flowers bloom from the bottom up and have a candle-like

appearance from a distance. Also called bog loosestrife or yellow loosestrife, these plants are in the

primrose family, not the loosestrife family.

Canada Lily, Lily family (Liliaceae), Native

|

|

|

Also known as wild yellow lily, Canada lily typically has spotted yellow flowers, as shown here, but

the flowers can also be orange or red.

Deptford Pink, Pink family (Caryophyllaceae), Alien

|

Deptford pink (Dianthus armeria) inhabits roadsides and dry fields. It has stiff, grass-like

leaves and small, deep pink flowers with a scattering of distinctive white spots. The half-inch blossoms

open only briefly during the middle of the day, so they are easy to miss. Sometimes called grass pink,

this plant came from Europe, probably as a garden escapee.

|

Pale-spike Lobelia, Bluebell family (Campanulaceae), Lobelia subfamily (Lobelioideae), Native

|

|

Shinleaf, Wintergreen or Pyrola family (Pyrolaceae), Native

|

Blooming in wooded areas in early July, shinleaf (Pyrola elliptica) is the most common pyrola. It

has several waxy white flowers. Each has a long pistil (female flower part) protruding from the center.

The term wintergreen has been used for several groups of plants, including the pyrolas. A different plant, known as checkerberry (Gaultheria procumbens), is the "wintergreen" that has been a source of oil of wintergreen, traditionally used for treating bodily aches and pains. Checkerberry has the characteristic "wintergreen" scent. It is in the heath family (Ericaceae). |

Spotted Wintergreen, Wintergreen or Pyrola family (Pyrolaceae), Native

|

|

The narrow, striped evergreen leaves of spotted wintergreen (Chimaphila maculata) are evident

at the Reservoir as soon as the snow has melted in the spring, but the blossoms usually do not appear

until July. These small plants are abundant in some areas, typically under pine trees. The nodding,

waxy blossoms are white or slightly pink.

The narrow, striped evergreen leaves of spotted wintergreen (Chimaphila maculata) are evident

at the Reservoir as soon as the snow has melted in the spring, but the blossoms usually do not appear

until July. These small plants are abundant in some areas, typically under pine trees. The nodding,

waxy blossoms are white or slightly pink.

Swamp-Honeysuckle or Swamp Azalea, Heath family (Ericaceae), Native

|

When a sweet fragrance wafts through the early summer air near a shore or streambank, chances are that

swamp-honeysuckle (Rhododendron viscosum) is in bloom in the nearby shrubbery. The white flowers are

large and lovely. In spite of its common name, this shrub is an azalea, not a honeysuckle. It belongs to

the heath family (Ericaceae), along with other azaleas, rhododendrons, and blueberries. It is also called

swamp azalea or clammy azalea.

When a sweet fragrance wafts through the early summer air near a shore or streambank, chances are that

swamp-honeysuckle (Rhododendron viscosum) is in bloom in the nearby shrubbery. The white flowers are

large and lovely. In spite of its common name, this shrub is an azalea, not a honeysuckle. It belongs to

the heath family (Ericaceae), along with other azaleas, rhododendrons, and blueberries. It is also called

swamp azalea or clammy azalea.

Partridgeberry, Bedstraw or Madder family (Rubiaceae), Native

|

In mid-July, pairs of small, funnel-shaped, white blossoms adorn the vines of partridgeberry (Mitchella repens), an evergreen creeper found in the woods at the Reservoir. Each pair of flowers later yields one berry, which turns red in the fall. The berries are apparently relatively low in nutritional value, since they can often still be found uneaten on the plants in the spring.

Native Americans used a tea made from partridgeberry leaves to speed childbirth, and this practice

spread among the European settlers. Because of this use, as well as others related to "female troubles,"

the plant was called squaw vine. One Native American group also used a tea from the plant to treat

insomnia.

Heal-all, Mint family (Labiatae), Alien

|

The small, light purple flowers of heal-all or self-heal (Prunella vulgaris) first appear along grassy paths in May, but the dense flowerheads can also be spotted in lawns, where mowing keeps the plants small. A member of the mint family, heal-all typically blooms throughout the summer. It spreads by runners as well as by seed.

The names heal-all and self-heal suggest abundant medicinal uses, and the plant was probably

brought to this continent for those uses. It was apparently used for wounds, sore

throats, and mouth ailments, although it is not a popular herbal remedy today. Research indicates

that it is high in antioxidants and contains substances that may be potentially useful

in medicine.

Jewelweed or Spotted Touch-Me-Not, Touch-Me-Not family (Balsaminaceae), Native

|

From mid-July through mid-September, jewelweed (Impatiens capensis) blooms in moist, partly shady areas of the Reservoir, particularly along streambanks. The numerous orange blossoms dangle like jewels from delicate stems. They develop into quarter-inch seed pods that pop open at a touch when they are ripe, providing great fun for kids and flinging seeds up to four or five feet away. These active seed pods give rise to the plant's other name, spotted touch-me-not.

Some people use jewelweed to treat the itch and rash from poison ivy. They pick leaves

and rub them on the affected skin, or they boil the plants in water and put the liquid on the rash.

Various Native American tribes used the plant for an assortment of skin ailments.

Pinesap, Wintergreen or Pyrola family (Pyrolaceae), Native

|

|

Checkerberry is the "wintergreen" that has been a source of oil of wintergreen, used in the past as a flavoring agent. Traditionally it was also applied externally to relieve bodily aches and pains. A tea from the leaves was used for colds, fevers, headaches, and stomach aches.

Broken leaves give off a recognizable wintergreen scent and have a wintergreen flavor. The chemical responsible for this wintergreen aroma and taste, methyl salicylate, is related to aspirin. This chemical is now made synthetically for commercial uses, such as flavoring.

Checkerberry is in the heath family (Ericaceae), along with blueberries, azaleas, and rhododendrons.

Wild Indigo, Pea family (Leguminosae), Native

|

|

|

Like beans, peas, and clovers, wild indigo is a legume. This group of plants is known for capturing

nitrogen--an important plant nutrient and a key ingredient in fertilizer--from the air and incorporating

it into a chemical form that plants can use. Legumes do this in partnership with certain kinds of

bacteria (Rhizobium), which they house and nourish in root nodules. Together, the plant and

the bacteria make a chemical that protects these bacteria from oxygen, which harms them. The bacteria,

in turn, make nitrogen available to the plant. This process also enriches the soil with nitrogen.

Fringed Loosestrife, Primrose family (Primulaceae), Native

|

Fringed loosestrife is the sturdiest of three yellow loosestrifes that bloom at the Reservoir in July. They are not members of the loosestrife family (Lythraceae), which includes purple loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria). Instead, they are all members of the primrose family (Primulaceae).

The name loosestrife comes from an old belief that certain plants could calm agitated animals

(loosen their strife), such as the oxen used for farm work.

Cardinal Flower, Bluebell family (Campanulaceae), Lobelia subfamily (Lobelioideae), Native

|

Cardinal flower may have been named either for the red of our native bird, the cardinal, or for the

robes of the cardinals of the Roman Catholic church. The scarlet flowers attract hummingbirds as well

as butterflies and a variety of other insects. This native North American wildflower spreads both by

seed and by shoots, which take two years to grow into mature flowering plants.

Marsh St. Johnswort, St. Johnswort family (Guttiferae or Hypericacaea), Native

|

|

|

Marsh St. Johnswort (Hypericum virginicum or Triadenum virginicum) is a wetlands wildflower, growing in wet, sandy soil near the water. In the long evenings of late July, its small nectar-laden

flowers open and then fade by morning. Most St. Johnsworts have yellow flowers, but this one has pink

flowers. Like other St. Johnsworts, its leaves are somewhat oblong and are dotted with tiny translucent

glands. The plant itself is low and bushy.

Purple Loosestrife, Loosestrife family (Lythraceae), Alien

|

|

|

| |

The naturalist Charles Darwin studied purple loosestrife extensively. The plant has three forms,

each with male and female flower parts of different sizes. These parts are arranged in ways that

prevent inbreeding as bees and other insects move among the flowers, transferring pollen.

Indian Tobacco, Bluebell family (Campanulaceae), Lobelia subfamily (Lobelioideae), Native

|

|

The small, inconspicuous purple flowers of Indian tobacco (Lobelia inflata) usually start to appear by the middle of the summer. The base of each flower eventually develops into a swollen seed pod, making it easy to distinguish the plant from other similar-looking ones. Indian tobacco is one of a few lobelias growing at the Reservoir, including the showy red cardinal flower and the pale-spike lobelia.

Animals avoid eating the plant because of its acrid taste. In the past Indian tobacco had medicinal

uses, but it may have worked best at inducing vomiting, as other names--such as

"puke weed"--suggest. Some Native Americans chewed and smoked the leaves, practices that

reportedly brought on drowsiness.

Downy Rattlesnake-plantain, Orchid family (Orchidaceae), Native

|

The flower spikes emerge from rosettes of dark green checkerboard-patterned leaves. The plants grow in patches on the steep hillsides leading up from the Reservoir. The distinctive leaves can be spotted throughout most of the year.

Like many flowers that grow on spikes, the blossoms at the bottom of each spike develop first, with higher blossoms opening progressively as time goes on. The male parts of the flowers mature first, producing a gooey, brightly colored pollen visible at the back of the flower. Female parts become receptive later, after pollen has been collected from the blossom. This timing helps to promote cross-pollination.

Small flying insects visit each flower spike in turn, starting at the bottom and working their way up the spike before moving on to another spike and starting at the bottom again. By moving in this way, foraging pollinators pick up pollen from newly opened blossoms near the top of one plant and then deliver it to more mature, receptive flowers at the bottom of the next plant. They then repeat the process as they continue up the spike to the younger flowers and acquire more pollen.

The blossom shown here has been visited in this manner. Tiny wasps approach the blossoms using the

tongue at the front of the slipper as a landing pad, their abdomens hanging down over the front of the

slipper. From there they explore the inside of the slipper, poking their heads far into the back of

the flower and into the gooey pollen. It sticks to their heads, and when they back out, they leave a

white hole behind in the yellow and brown pollen mass at the back of the flower. The blossom then

continues to mature, later becoming receptive to pollination.

Black Nightshade, Nightshade or Potato family, Alien

|

|

Perhaps because both plants have black berries, black nightshade is sometimes mistaken for true "deadly nightshade," which is actually a different plant, belladonna (Atropa belladonna). Belladonna contains a poisonous chemical, atropine. It grows in central and southern Europe but is rare in North America.

In spite of its reputation for possible toxic effects, black nightshade has a history of medicinal use.

It has also served as food. The ripe berries have been added to pies in the midwest, and its boiled

leaves have been used for food by people in this country, Europe, and parts of Asia. Grazing animals,

however, avoid eating the greens. For safety's sake, children should not put the berries in their mouths.

Square-stemmed Monkey-flower, Snapdragon or Figwort family (Scrophulariaceae), Native

|

Bluecurls, Mint family (Labiatae), Native

| The low plants of bluecurls (Trichostema dichotomum), found in dry clearings at the Reservoir, bloom profusely after summer rains in August. The notable long "blue curls" are actually the flowers' stamens (male flower parts). This small, easily missed plant is a member of the mint family. |

Beaked Hazelnut

|

Beaked Hazelnut (Corylus cornuta) is noticeable in the woods in late summer or early fall not because

of flowers but because of its nut, which has an unusual beaked-shaped husk. The nuts are edible but popular

with wildlife so they may be hard to find in the fall. These and other hazelnuts have been roasted as a snack,

ground into flour, and candied.

Orange Hawkweed, Composite or Daisy family (Compositae), Alien

|

Orange hawkweed (Hierarium aurantiacum), commonly called devil's paintbrush, blooms sporadically in fields at the Reservoir in the summer. It can also be spotted in other Westborough locations, such as the lawn at Hastings Elementary School, as early as June. The flower looks somewhat like an orange dandelion.

The plant has some of the same unpopular characteristics as the dandelion: it can spread quickly, is

hard to get rid of, and can choke out other plants. Farmers in the midwest despise it because it can

quickly take over entire fields, forming tough mats on the ground. The plant came to this continent

from Europe, probably traveling with crop seeds.

Common Evening-Primrose, Evening-Primrose Family (Onagraceae), Native

|

This hardy plant is biennial, living for two years. The first year it grows as a rosette or low cluster of leaves, and the second year it sends up a tall flower stalk and blooms. Its deep tap root can be boiled and eaten the first year, and its young leaves can be used in salads or cooked as greens. In the early 1600s, colonists sent this native plant back to Europe, where it was then cultivated as food.

Common evening primrose had medicinal uses among Native Americans, who made a root tea from it and also used

the root in poultices and as a rub. The seed oil is a good source of gamma-linolenic acid, which the human body

needs. Modern research has found that the seed oil may be helpful in treating eczema and a range of other

ailments. It is licensed in England for treating skin inflammation, premenstrual syndrome (PMS), and

breast pain.

Goldenrod, Composite or Daisy family (Compositae), Native

|

| |

Goldenrod is often wrongly blamed for causing hay fever, probably because it blooms during the height of hay fever season. In fact, most hay fever is caused by ragweeds, such as common ragweed (Ambrosia artemisiifolia) and great ragweed ( Ambrosia trifida,). Unlike goldenrod, these ragweeds are wind-pollinated. They produce vast quantities of tiny, light pollen that readily becomes airborne. Goldenrod pollen is heavier and better suited for transport by bees.

People who pick goldenrod for late-summer bouquets may sometimes be surprised to discover that they have also brought home insects. A single goldenrod plant can contain a diverse insect community. Goldenrod flowers offer a rich supply of nectar, especially as other sources begin to dwindle with the approach of fall. The flowers attract bumblebees and honey bees, as well as flies that resemble them, complete with yellow and black stripes. Butterflies, ants, and wasps also frequent goldenrod.

Predatory insects often hunt in goldenrod. They include yellow jackets and the yellow goldenrod spider

( Misumena vatia), which is one of the 200 crab spiders (Thomisidae family) that are colored like

the flowers they hide in. Instead of spinning a web to trap prey, crab spiders lie in wait, camouflaged,

and grab and paralyse other insects. Another typical predator is the yellow ambush bug

(Phymata crosa), which also hides and seizes insect prey. Goldenrod plants may also harbor a

type of "praying mantis", which also consumes insects.

Wild Mint, Mint family (Labiatae), Native

|

|

|

Wild mint (Mentha arvensis) grows on wet shores of the Reservoir. The plants have the characteristic square stem of mints, a scent of mint, and clusters of small fuzzy-looking flowers growing where leaves and stems meet. The flowers can be light purple or white, and both are found at the Reservoir. The plants spread by underground runners and can form colonies.

Wild mint is native to North America, unlike spearmint (Mentha spicata) and peppermint

(Mentha piperita), which come from Europe and bear flowers on spikes. Native Americans used

wild mint as a tea and as a flavoring for meats, much as we do today with various mints, especially

spearmint. Some Native American groups used wild mint to treat nausea.

Swollen Bladderwort, Bladderwort family (Lentibulariaceae), Native

|

|

|

|

Floating inconspicuously in shallow water along the shores of the Reservoir, small swollen bladderwort plants (Utricularia inflata) can appear as early as July. They usually become much more abundant as water levels drop during the advancing summer. This aquatic plant bears small, yellow, snapdragon-like flowers and has a whorl of inflated, spoke-like leaf stalks that serve as floats. The plant is only a few inches high.

Like other bladderworts, swollen bladderwort is a carnivorous plant. Some of its underwater parts bear

numerous tiny bladders, each with a trap door and a hair-like trigger, that capture and digest minute

water organisms, such as insect larvae and tiny crustaceans. Like showier and more well-known

carnivorous plants such as the Venus flytrap, bladderworts have evolved to get certain nutrients,

such as nitrogen, from tiny organisms rather than from the soil or water. The reason is that the acidic

environments in which they usually grow tend to be poor in such nutrients.

Virginia Meadow-Beauty or Deer Grass, Meadow-Beauty family (Melastomataceae), Native

|

In sunny, wet, sandy areas, such as the stream bed near the Reservoir when water levels are low, Virginia meadow-beauty (Rhexis virginica) blooms in late summer. The deep rose-colored flowers look slightly lopsided. Drooping from their centers are distinctive long, thin, yellow anthers (male, pollen-bearing parts) and a long curving pistil (female flower part, white in the photo). The flowers are showy, like many other members of the largely tropical meadow-beauty family.

The leaves grow in pairs and have obvious parallel ribs. They turn red in the fall. Also called deer grass, the plant is supposedly a favorite food of deer in more western parts of the country.

To get pollen from meadow-beauty flowers, bees such as bumblebees must hang on and vibrate the pollen

out of the anthers, using their wing muscles. After a day or so in bloom, the yellow anthers change

color, becoming duller. While an older flower is still showy enough to attract bees to its

vicinity--where other, fresher meadow-beauty flowers also grow--the color change may help to signal

to pollinators that the older flower's pollen has already been used up.

Spotted Joe-Pye-weed, Composite or Daisy family (Compositae), Native

|

Along the edges of sunny, swampy areas, stands of spotted Joe-Pye-weed (Eupatorium maculatum) become apparent in August. These tall plants have flat-topped clusters of closely packed purple flowers. They lend color to any landscape that includes stands of them. The flowers attract bees and butterflies, but the plant can also pollinate itself as the flower parts brush against one another.

The plant is named for Joe Pye (or Jopi), who, according to folklore, was a traveling Native American medicine man. He lived in New England around the time of the American Revolution and may have been from a tribe in Maine. He sold various herbal remedies to the colonists and apparently treated typhoid fever with the plant that bears his name to this day.

There are a few different species of Joe-Pye-weed, but spotted Joe-Pye-weed is the most common. It has

a deep purple or purple-spotted stem, unlike other varieties.

Butter-and-eggs, Snapdragon or Figwort family (Scrophulariaceae), Alien

|

Butter-and-eggs spreads both by seed and by underground stems called rhizomes, and it can form large colonies. It needs to grow among other plants because it is parasitic. Its roots tap into other plants' roots, taking water and salts but without killing the other plants.

Although the butter-and-eggs had medicinal uses in the past, its juice was also mixed with milk to make a

fly poison. The flowers have been a source of yellow dye.

Fern-leaved False Foxglove, Snapdragon family (Scrophulariaceae), Native

|

In late summer, fern-leaved false foxglove (Gerardia pedicularia) makes itself known by its showy yellow trumpet-shaped blossoms. As the name suggests, the plant has lacy, fern-like leaves, unlike other false foxgloves. False foxgloves typically grow near oak trees, since they are partially parasitic on the roots of oaks.

Although they are in the same family, false foxgloves are not the same as cultivated foxglove

(Digitalis purpurea), a garden plant imported from Europe in colonial times and well known as the source

of digitalis, a powerful heart medicine. The flowers bear some resemblance to one another. False foxgloves

do not provide digitalis.

Boneset, Composite or Daisy family (Compositae), Native

|

|

|

Boneset (Eupatorium perfoliatum) flowers in sunny, wet places in August, but the large plants are evident long before. Growing up to five feet tall, the hairy plants are distinguished by large, wrinkled leaves that look as if the plant stem is growing right through them. In reality, the leaves in a pair grow opposite one another and are joined at the base.

In bygone days, boneset tea was a well-known household remedy for fever and colds, in spite of its unpleasant

taste. People commonly gathered the plants and hung them to dry in attics and barns so families would have them

on hand in case someone fell ill. The name boneset may come from the plant's use in treating dengue fever,

also called bone-break fever because of the terrible pains that accompanied it. The leaves may also have been

part of the wrapping for broken bones.

Purple Bladderwort, Bladderwort family (Lentibulariaceae), Native

|

Purple bladderwort is a carnivorous aquatic plant with small purple flowers. Its underwater leaves are like

networks of filaments, with small pods--the trap-like bladders--scattered among them. Each bladder has a

trap door and a hair-like trigger. Tiny water organisms, such as insect larvae and tiny crustaceans, get

sucked into the bladder when the trap door opens suddenly. These creatures are digested in the

bladders, providing certain key nutrients, such as nitrogen, to the plant. The plants are only a few inches

high, but their underwater networks can be extensive.

Marsh Speedwell, Snapdragon family (Scrophulariaceae), Native

|

Speedwells typically spread quickly, both by underground runners and by seed. The flowers can also fertilize themselves, so they produce seeds even when they have not been pollinated in the normal course of events. Their rapid spread may have earned them the name speedwell.

Speedwells have historically been put to numerous medicinal uses, both interally and externally. Not

surprisingly, these uses are another likely source of the name speedwell.

Turtlehead, Snapdragon or Figwort family (Scrophulariaceae), Native

|

Nestled here and there along the banks of the stream that feeds the Reservoir, turtleheads (Chelone glabra) make their appearance around the first week of September. The plants are perennials, so they can usually be found in the same spots year after year. The large one-to-two-inch white blossoms are sometimes tinged with pink.

The plant gets its name from the shape of the flowers. They look somewhat like the head of a turtle. The top of the flower resembles the shape of a turtle's shell.

Turtleheads are pollinated mainly by large bees, which can force their way into the flowers. As a bee pokes around inside a flower, in search of nectar, the flower moves in such a way that it can look like it is chewing something--an amusing sight.

Turtleheads are related to butter-and-eggs and to garden snapdragons. Pink or purple species grow in

the southern states.

Closed Gentian, Gentian family (Gentianaceae), Native

|

The markings around the small opening at the tops of the flowers provide cues for bees. The newer flowers in a cluster, which are well supplied with nectar, are white at the very tips of the closed petals, marking the entrance for the bees. Older blossoms turn blue-purple around the opening, and bees no longer visit them.

A similar species, Andrew's bottle gentian

(Gentiana andrewsii), is also found in New England but is rare in our area. The two species

are almost indistinguishable without close inspection. One way to tell the two apart is to examine

the flowers by spreading the tips open. In both species the petals are joined by a

fringed membrane. In Gentiana clausa the fringe comes up to the tips of the petals, whereas

in Gentiana andrewsii the fringe is longer than

the petals. Only Gentiana clausa grows at the Reservoir.

Nodding Ladies'-tresses, Orchid family (Orchidaceae), Native

|

Early autumn brings out low spikes of small white orchids, known as common or nodding ladies'-tresses (Spiranthes cernua). Growing about 18 inches high in sunny, sandy areas near water, the plants bear numerous blossoms on a twisting stem. The name "ladies'-tresses" is due to the way the flowers seem to be woven into the stem, as if in a braid or "tress". The flowers are "nodding" because they point slightly downward, an arrangement that keeps rain out, preventing the nectar from becoming diluted. The flowers have a sweet fragrance that attracts bees.

As in many other plants that flower in spikes, the flowers open progressively from the bottom of the spike up. This sequence puts the newer flowers, which produce pollen, at the top of the spike and the older, more mature flowers, which are ready to receive pollen, at the bottom. This set-up suits bees' habit of climbing up a spike of flowers and then starting again at the bottom of the next spike. In the process, the bees transfer pollen from the younger flowers at the top of one plant to the older, receptive flowers at the bottom of the next plant.

The nodding ladies'-tresses have evolved even more specific ways of ensuring that bees transfer pollen. Bees gather nectar with their tongues. When a bee visits a new flower, its tongue splits open a disk inside the flower, releasing a sticky glue that helps clumps of pollen stick to the bee's tongue. Then, when the bee goes to the bottom of the next spike, it visits older flowers in which the split has widened enough to expose the flower's pollen-receiving parts, which pick up the pollen already stuck to the bee's tongue.

Like other orchids, nodding ladies'-tresses may need certain soil fungi to grow.

Downy Goldenrod, Composite or Daisy family (Compositae), Native

|

The goldenrods of late summer come in many shapes: plume-like, elm-branched, club-like, wand-like, and

even flat-topped. Downy goldenrod (Solidago puberula) blooms in well filled-out wands that have

a downy look. The flowerheads are somewhat larger than those of many other goldenrods, so it is easy to

see that they are daisy-like. Blossoms at the top of the wand open first, unlike so many other plants

with flower spikes that usually bloom from the bottom up. Downy goldenrod favors sunny, dry, sandy areas.

|

Asters, Composite or Daisy family (Compositae), Native

|

September is the month for asters--"stars"--at the Reservoir and everywhere else. Asters bloom abundantly,

and there exist many different species of aster, which are often tricky to tell apart. The asters of

September are usually blue or purple with bright yellow centers that may turn purple or brown with time.

Some species close at night.

|

|

|||

|

Asters at the Reservoir include stiff aster (Aster linariifolius), smooth aster

(Aster laevis), and New York aster (Aster novae belgii).

Common Witch Hazel, Witch Hazel family

|

According to folklore, forked branches of witch hazel were cut and used as divining rods to find

water underground. The bark of witch hazel has also provided ingredients for soothing skin ointments.

Allen, Kristina Nilson, On the Beaten Path: Westborough, Massachusetts, Westborough Civic Club and Westborough Historical Society, 1984.

"Ants and Plants," USCS Herbarium - Ants and Plants, University of South Carolina Spartanburg, 2001, http://www.uscs.edu/academic/colla&s/herbarium/ants.htm, 2/23/02.

Bernhardt, Peter, The Rose's Kiss: A Natural History of Flowers, Island Press, Washington, D.C., 1999.

Culley, Theresa M., "Why Violets Are So Successful", The Violet Gazette, Autumn 2000, Volume 1, Number 4, p. 4, American Violet Society, 2/23/02.

Culver, David C., and Beattie, Andrew J., "Myrmecochory in Viola: Dynamics of Seed-Ant Interactions in Some West Virginia Species," Journal of Ecology, Volume 66, Issue 1 (Mar., 1978), 53-72.

Dwelley, Marilyn J., Spring Wildflowers of New England, Down East Enterprise, Inc., Camden, Maine, 1973.

Dwelley, Marilyn J., Summer and Fall Wildflowers of New England, Down East Enterprise, Inc., Camden, Maine, 1977.

Foster, Steven, and Duke, James A., A Field Guide to Medicinal Plants and Herbs of Eastern and Central North America, Second Edition, Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston, 2000.

Kricher, John C., and Morrison, Gordon, A Field Guide to Eastern Forests, Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston, 1972.

Newcomb, Lawrence, Newcomb's Wildflower Guide, Little, Brown, & Co., Boston, 1977.

Peterson, Lee Allen,Edible Wild Plants of Eastern and Central North America, Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston, 1977.

Peterson, Roger Tory, and McKenny, Margaret, A Field Guide to Wildflowers of Northeastern and North-Central North America, Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston, 1968.

Petrides, George A., A Field Guide to Trees and Shrubs, Second Edition, Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston, 1972.

Sanders, Jack, Hedgemaids and Fairy Candles: the Lives and Lore of North American Wildflowers, Ragged Mountain Press, Camden, Maine, 1993.

Stomberg, Richard. "Carnivorous Plants of New England," New England Wild Flower, vol. 4, no. 1, spring/summer 2000, pp. 4-5.

Thieret, John W., Niering, William A., and Olmstead, Nancy C., National Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Wildflowers, Revised Edition, Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., New York, 2001.

Weiner, Michael A., Earth Medicine, Earth Food, Ballantine Books, New York, 1980.

New England Wild Flower Society

The North American Native Plant Society

and Wildflower Magazine

Westborough Charm Bracelet

- Project linking 26 miles of local trails. Trail maps online.

| Photo Index Other Local Wildflowers Wildlife Photos from the Reservoir Other Wildflowers Our main wildflower site Our other photography pages

|  Home /

Contact

Home /

Contact

| |

| Copyright © Anne A. Reid 1999-2002 Photographs copyright © Garry K. Kessler 1999-2002 |

|

|

|