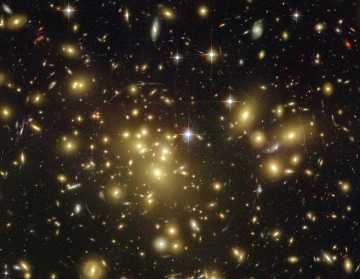

PHOTO COURTESY OF NASA Hubble/ACS photo

This massive cluster of galaxies is known as Abell 1689. Look for spiral galaxies like our own Milky Way. Note also the curved streaks of light, due to the bending of light by gravity.

March 20, 2009, Page 11

NATURE NOTES

By Annie Reid

Westborough Community Land Trust

Looking Up

Winter is a time for looking up, but that time didn’t end when spring officially arrived this morning at 7:44 a.m.

Not only do we see more of the sky during winter and early spring because the leaves are off the trees, but cold clear nights also give us a particularly crisp view of the night sky. The heat and humidity of warmer months tend to obscure the view, making it fuzzy.

The cold clear nights that are so good for stargazing become less frequent in spring, but we still have time to take advantage of them.

The lights of developed and urbanized areas – streetlights, house and building lights, cars, and so on – also make it difficult to get a good look at the night sky. Even in Westborough, this “light pollution” from the surrounding area makes it hard to see our very own galaxy, the Milky Way. For that view, people in western Massachusetts have better luck.

But there are always things to see with the naked eye in the night sky. There’s the moon, of course. It was full last week, on March 10. The “worm moon” is one of the traditional names for the March full moon. This name came to us from Native Americans and early colonists and reminds us of the life that stirs in the warming soil of spring.

This month Saturn is bright in the night sky. It lined up opposite the sun on March 8, and it was also at its closest point to Earth at that time.

March is the last month to see Venus shining steadily as the “evening star” in the west after sunset. After March 27 it won’t be visible at all, but then in April it will reappear, this time near sunrise as the “morning star.” In fact, if you want a preview, on March 25 and 26 you can see it as both the evening star and the morning star, low in the sky after sunset and before sunrise.

Various constellations are also visible, not only to us but also to birds that migrate at night. Early in life, many of these birds – with their keen eyesight – learn the constellations that are near the North Star and appear to rotate around it in the night sky. The birds then use these constellations (such as the Big Dipper and Little Dipper) to head in the correct directions during their spring and fall migrations.

PHOTO COURTESY OF NASA Hubble/ACS photo

Abell 2218 is a cluster of galaxies 2 billion light-years away. The curved streaks of light are distorted images of even more distant galaxies.

How do we know this? In the 1950s and 1960s, researchers did experiments with caged birds in a planetarium and found that some migrating birds use the stars as a compass. The researchers changed the sky in the planetarium and observed the direction in which the birds tried to go at migration time. They also noticed that if some constellations were covered, as might happen on a partly cloudy night, the birds used the others to face in the right direction.

The sky also contains amazing sights that we can’t see with the naked eye. Some backyard observers use telescopes or even binoculars, but for some sights we need to get beyond the obscuring effects of Earth’s atmosphere. Fortunately, anyone can look at published photos taken from the NASA Hubble space telescope, which orbits Earth.

In the color photograph from Hubble we can see something other than stars. We can actually see many galaxies, which are large collections of stars, gas, and dust. Some are spiral galaxies, like our own Milky Way. If you look carefully, you can spot the arms spiraling out from the center of these galaxies.

Notice that there are also faint, curved streaks of light in the color photo. These arcs of light are easier to see in the black and white photo, also from Hubble. They look as if they don’t belong in a photo of outer space, but they are not distortions from the camera or the telescope. Amazingly, they are due to the bending of light by gravity – something that Einstein predicted back in 1916.

An effect that astronomers call “gravitational lensing” creates the curved streaks of light in these photos. Einstein predicted that light bends as it passes by strong gravitational fields. The arcs of light in each photo surround galaxy clusters that have immense gravitational fields. As light passes by the galaxy clusters, it is bent – in much the same way as it’s bent when it passes through a lens in eyeglasses. The arcs of light in the photos are actually the distorted images of distant galaxies.

Who would have thought that we would be able to see Einstein’s prediction in a photograph?

For more amazing photographs, check out the Hubble web site: http://hubblesite.org.